2025-11-25 19:11:11

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) majorpublished

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Karen Pendergrass is a microbiome researcher specializing in microbiome-targeted interventions (MBTIs). She systematically analyzes scientific literature to identify microbial patterns, develop hypotheses, and validate interventions. As the founder of the Microbiome Signatures Database, she bridges microbiome research with clinical practice. In 2012, based on her own investigative research, she became the first documented case of FMT for Celiac Disease—four years before the first published case study.

Giorgos — BSc, MSc. Giorgos is an exercise scientist whose training and professional practice sit at the intersection of human performance, clinical health, and emerging microbiome science. He holds a BSc in Sports Science & Physical Education from Aristotle University (2012) and an MSc in Exercise & Health from Democritus University (2016), where his graduate work explored physiological adaptations to training across the lifespan. Now in his 15th year of practice, Giorgos pairs evidence-based coaching (ACSM-CPT, NSCA, USA Weightlifting) with a research-driven interest in how physical activity, body composition, and musculoskeletal integrity shape—and are shaped by—host–microbiome dynamics.

Microbiome-targeted interventions (MBTIs) are validated using a dual-evidence logical framework. First, the intervention must realign the condition’s microbiome signature by increasing beneficial taxa that are consistently depleted and reducing pathogenic taxa that are consistently enriched. Second, the intervention must demonstrate measurable clinical benefit. Concordance of these effects in the same context validates the intervention as an MBTI and supports the clinical relevance of the microbiome signature.

Microbiome Signatures identifies and validates condition-specific microbiome shifts and interventions to accelerate clinical translation. Our multidisciplinary team supports clinicians, researchers, and innovators in turning microbiome science into actionable medicine.

Karen Pendergrass is a microbiome researcher specializing in microbiome-targeted interventions (MBTIs). She systematically analyzes scientific literature to identify microbial patterns, develop hypotheses, and validate interventions. As the founder of the Microbiome Signatures Database, she bridges microbiome research with clinical practice. In 2012, based on her own investigative research, she became the first documented case of FMT for Celiac Disease—four years before the first published case study.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration. [1][2] Loss of microbial diversity, diminished short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing genera such as Faecalibacterium, Roseburia, and Ruminococcus, and increased indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate producers heighten intestinal permeability, systemic inflammation, and endotoxemia, all of which intensify kidney injury. [3] Evidence from fecal microbiota transplantation studies demonstrates that CKD-derived microbiota can directly promote renal fibrosis, supporting a dose-response relationship where the abundance of uremic toxin precursor species rises with advancing CKD and drives progressive renal damage. [4]

Associated conditions in chronic kidney disease encompass a broad spectrum of interrelated systemic complications that emerge early in renal impairment and intensify as kidney function declines. These complications reflect the kidney’s central role in metabolic, endocrine, cardiovascular, neuromuscular, and immunologic homeostasis, and their cumulative burden profoundly shapes patient outcomes. As dysregulated uremic metabolism, chronic inflammation, mineral imbalances, and microbiome disturbances converge, patients develop a characteristic pattern of comorbidities that includes cardiovascular disease, metabolic dysfunction, anemia, mineral bone disorder, neurocognitive decline, sarcopenia, and heightened infection susceptibility. The prevalence and severity of these conditions rise sharply across CKD stages, underscoring the need for early recognition, mechanistic understanding, and integrated therapeutic strategies.

Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of morbidity and mortality in CKD, which independently increases the risk of atherosclerotic disease, hypertension, left ventricular hypertrophy, heart failure, and sudden cardiac death. [5]

These complications arise through a combination of traditional risk factors and CKD-specific drivers that include uremic toxin accumulation, mineral bone disorder, vascular calcification, and systemic inflammation. [6]

Mortality risk is markedly elevated, with patients in CKD stages 4-5 experiencing a 10 to 20-fold higher cardiovascular death rate than age-matched controls, and cardiovascular events frequently occurring even without obstructive coronary disease. Cardiac remodeling in CKD is mediated through neurohormonal activation, sympathetic dysregulation, mitochondrial dysfunction, and oxidative stress. [7]

Silent myocardial ischemia affects roughly 37 to 40 percent of CKD stage 3-5 patients and correlates with age, diabetes, left ventricular hypertrophy, and increased parathyroid hormone concentrations. Left ventricular hypertrophy is present in 70 to 80 percent of CKD patients and constitutes a major independent determinant of cardiovascular risk.[8]

Type 2 diabetes mellitus and metabolic dysfunction occur with markedly elevated prevalence in CKD populations, with approximately 30-40% of CKD patients having underlying diabetes as either primary or concurrent disease. [9]

Conversely, CKD substantially increases diabetes incidence and accelerates progression of hyperglycemia toward insulin resistance, with dysbiosis-mediated changes in glucose metabolism and incretin signaling contributing to metabolic dysfunction independent of baseline glycemic control. [10]

Dysbiosis reduces short-chain fatty acid (SCFA) production, impairing GPR41/GPR43 signaling necessary for maintaining glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity.

Insulin resistance plays a central role in both CKD pathogenesis and progression of metabolic complications.[11]

Bone and mineral metabolism disorders (CKD-mineral bone disorder, CKD-MBD) affect >80% of CKD stage 4-5 patients, encompassing secondary hyperparathyroidism, phosphate retention, vitamin D deficiency, vascular calcification, and adynamic bone disease. [12] These complications result from impaired renal phosphate excretion, altered fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) signaling, disrupted parathyroid hormone responsiveness, and dysbiosis-mediated dysregulation of mineral-sensing pathways. [8] CKD-MBD increases fracture risk, impairs fracture healing, and independently predicts cardiovascular events and mortality in CKD populations.

Adynamic bone disorder, defined by reduced bone turnover with low parathyroid hormone levels, develops in a substantial proportion of advanced CKD patients and is induced by medications such as calcimimetics and high-dose vitamin D analogs.[14] Uremic toxins like indoxyl sulfate contribute to PTH hyporesponsiveness, exacerbating bone turnover abnormalities. Vascular calcification represents a distinct manifestation of CKD-MBD that is associated with increased cardiovascular events and mortality independent of bone mineral density measurements.

Anemia is highly prevalent in CKD, affecting approximately 30-40% of stage 3-5 patients and more than 60% of dialysis patients, resulting from decreased erythropoietin production, uremic toxin accumulation, and chronic inflammation. [15].

The prevalence and severity of CKD-related anemia increase progressively with declining kidney function, with hemoglobin levels and hematocrit inversely correlated with CKD progression risk. [16]Anemia in CKD is associated with increased cardiovascular events, cognitive impairment, fatigue, and reduced quality of life.

Optimal hemoglobin maintenance of 110-130 g/L in CKD stages 3-4 demonstrates protective effects in delaying disease progression. [17] Anemia determinants in CKD include comorbidities such as diabetes, prolonged dialysis duration, declining kidney function, and biomarkers including ferritin and inflammatory markers. [18]

Cognitive impairment is increasingly recognized as a significant complication of CKD, with prevalence increasing substantially with declining kidney function.[19] The prevalence of cognitive impairment reaches approximately 10% at eGFR ≥60 mL/min/1.73m², 47.3% at eGFR 60-30 mL/min/1.73m², and 60.6% at eGFR <30 ml min 1.73m². t2dm, cardiovascular diseases, cerebrovascular and lower education emerge as strong predictors of cognitive decline risk, with odds ratios 1.55, 1.63, 1.95, 2.59, respectively.[20]

Depression and anxiety disorders occur with significantly elevated prevalence in CKD populations, with vitamin D deficiency identified as an independent risk factor. CKD patients with vitamin D deficiency demonstrate a hazard ratio of 1.929 for major depression at one-year follow-up compared to those with adequate vitamin D levels, with this association persisting through three years of follow-up.[21]

Sarcopenia, defined by reduced skeletal muscle mass, strength, and physical performance, develops in 5-15% of non-dialysis CKD patients and 45-77% of dialysis patients depending on diagnostic criteria applied.[x]

CKD-related sarcopenia results from accelerated protein catabolism, inadequate nutritional intake, physical inactivity, and chronic inflammation. The triglyceride-glucose index, a marker of insulin resistance, is positively associated with sarcopenia risk in CKD patients, with 3-4 fold increased sarcopenia risk in highest versus lowest TyG quartile groups.[x]

Sarcopenia in CKD is associated with poor physical function, increased fall risk, fractures, reduced quality of life, and higher mortality rates. Polypharmacy and hyperpolypharmacy are independently associated with low muscle strength in dialysis patients.[24]

Chronic kidney disease is increasingly understood as a condition shaped not only by impaired renal filtration but by a complex interplay between dysbiotic microbial communities, disrupted metabolite production, and altered metallomic homeostasis. As renal function declines, shifts in gut microbial composition generate pathogenic metabolites, weaken mucosal barrier integrity, amplify systemic inflammation, and modify host pathways involved in cardiovascular, metabolic, and neuroimmune regulation. Complementary but distinct conceptual hypotheses have emerged, including metabolic endotoxemia, dysbiosis-driven uremic toxin generation, toxic metal-driven metallomic dysbiosis, essential metal deficiency, TMAO-mediated cardiovascular injury, RAAS dysregulation, and disruption of the tryptophan-AhR axis. Together, these frameworks describe how altered microbial communities, their metabolites, and their metal handling properties converge on shared pathophysiological endpoints, including intestinal barrier failure, chronic inflammation, cardio-renal remodeling, neuropsychiatric impairment, and accelerated CKD progression.

Chronic lipopolysaccharide (LPS) translocation from dysbiotic gram-negative bacteria into systemic circulation induces persistent low-grade endotoxemia characterized by elevated circulating lipopolysaccharide-binding protein and soluble CD14 levels. This systemic endotoxemia drives chronic inflammation through TLR4 activation on macrophages and endothelial cells, directly contributing to obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction, insulin resistance, and accelerated CKD progression independent of baseline kidney function.[25]

These interconnected mechanisms collectively establish that dysbiosis and aberrant microbial metabolite production represent central drivers of CKD pathophysiology, positioning microbiota-targeted interventions as promising therapeutic avenues for slowing disease progression and reducing complication burden across CKD populations. [26]

The dysbiosis-uremic toxin hypothesis posits that dysbiotic microbiota dysregulation represents a primary driver of CKD progression and associated systemic complications through generation of protein-derived uremic toxins. [27]

In this mechanistic model, impaired renal function reduces uremic toxin clearance, creating a permissive uremic milieu that selectively favors growth of dysbiotic bacteria capable of producing indoxyl sulfate (IS), p-cresyl sulfate (pCS), and other protein-bound uremic toxins while suppressing short-chain fatty acid-producing commensals.[28]

These dysbiotic metabolites accumulate systemically, perpetuating a vicious cycle where uremic toxins further damage intestinal barrier integrity, promote pathogenic bacterial bloom, and accelerate both renal function decline and systemic complications including cardiovascular disease, neuroinflammation, and oxidative stress damage to peripheral nerves. [29]

The Metallomic Dysbiosis Axis in CKD hypothesis

extends beyond traditional uremic toxin mechanisms by proposing that toxic metal accumulation in CKD creates selective environmental pressure favoring metal-resistant dysbiotic bacteria while suppressing metal-sensitive beneficial commensals. Elevated uremic concentrations of cadmium and lead that reach the intestinal lumen through enterohepatic circulation activate bacterial metal efflux pump expression and metallothionein production, with metal-resistant Enterobacteriaceae expanding while short-chain fatty acid-producing bacteria are suppressed. [30]

This dysbiotic expansion is compounded by metal-induced oxidative damage to intestinal epithelial cells, creating synergistic barrier dysfunction that promotes bacterial translocation independent of traditional dysbiotic lipopolysaccharide and uremic toxin effects. Studies characterizing the CKD microbiota have identified lead and arsenic-resistant bacteria as dominant genera in stage 3 CKD patients, with multiple antibiotic and metal resistance genetic markers including cadA and arsC genes, suggesting that metal selective pressure directly shapes dysbiotic composition.[31]

The essential metal deficiency hypothesis proposes that dysbiosis-driven impairment of metal-dependent bacterial metabolism contributes to systemic complications in CKD through dual mechanisms of reduced essential metal bioavailability and dysbiotic-mediated dysregulation of metal-dependent biochemical pathways [8]. Dysbiotic microbiota exhibit reduced zinc-dependent antimicrobial peptide production and dysregulated zinc-dependent tight junction protein expression (claudin-1, ZO-1), directly impairing intestinal barrier integrity independent of systemic zinc status.[32]

Zinc homeostasis in intestinal epithelial cells is critical for maintaining host-microbiome symbiosis; dysbiotic dysregulation of zinc transporters compromises both barrier function and the capacity of specialized Paneth cells to produce antimicrobial defenses, thereby facilitating bacterial translocation and perpetuating systemic inflammation.[33]

The trimethylamine-N-oxide (TMAO) hypothesis proposes that dysbiotic-mediated production of TMAO from dietary choline and L-carnitine represents a key mechanistic link between dysbiosis and cardiovascular complications in CKD.[34]

In healthy individuals, intestinal bacteria generate trimethylamine from dietary precursors, which undergoes hepatic oxidation to TMAO; however, dysbiotic microbiota exhibit altered TMAO production rates and modified microbial metabolic capacity.[35]

Elevated TMAO concentrations in CKD inhibit cholesterol reverse transport, promote platelet aggregation and thrombosis, induce endothelial dysfunction through oxidative mechanisms, and activate sterile inflammation through NLRP3-inflammasome-dependent pathways, thereby substantially contributing to the 10-20 fold increased cardiovascular mortality observed in CKD populations.[36]

TMAO additionally promotes vascular stiffness and reduced arterial compliance, key mechanisms by which CKD patients develop left ventricular hypertrophy and heart failure independent of traditional hypertension severity.[37]

Dysbiosis impairs microbial production of ACE2-activating metabolites and dysbiotic-derived metabolites promote angiotensin II-mediated renal injury through enhanced TGF-β signaling. [38][39]

In healthy individuals, commensal bacteria produce metabolites that promote intestinal and systemic ACE2 expression; dysbiotic microbiota fail to produce these metabolites, reducing ACE2 availability and allowing unopposed angiotensin II accumulation.[40]

Dysbiotic-derived lipopolysaccharides directly impair renal AMPK signaling through TLR4 activation, reducing AMP-dependent protein kinase-mediated inhibition of mTOR pathway and promoting fibrotic signaling through dysregulated metabolic sensing. [41]

Additionally, dysbiotic dysregulation of secondary bile acid-mediated TGR5 signaling reduces renal AMPK activation and G-protein coupled receptor signaling, promoting intrarenal inflammation and fibrotic responses. [42]

These interconnected dysbiotic effects on RAS dysregulation directly contribute to progressive renal dysfunction through enhanced vasoconstriction, sodium retention, and pathogenic cardiac and renal vascular remodeling.

The tryptophan-aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) axis dysfunction theory proposes that dysbiosis-mediated loss of tryptophan-metabolizing bacteria reduces production of AhR-activating metabolites (indole-3-aldehyde, indole-3-propionic acid, kynurenine) that normally support intestinal IL-22-producing immune responses and maintain mucosal immunity. [43]

Dysbiotic microbiota demonstrate reduced tryptophanase and other tryptophan-metabolizing enzyme expression, creating deficiency in AhR ligands that ordinarily activate group 3 innate lymphoid cells (ILC3) to produce IL-22, a critical cytokine maintaining intestinal epithelial barrier integrity and antimicrobial peptide production. [44]

This AhR-axis dysregulation in dysbiotic CKD populations contributes to increased intestinal permeability, bacterial translocation, loss of neuroprotective metabolites that normally support blood-brain barrier integrity, and reduced capacity for intestinal antimicrobial defense against pathogenic blooms, ultimately exacerbating both renal disease progression and the neuropsychiatric complications characteristic of advanced CKD.

The interplay between metal homeostasis, microbial dysbiosis, and metabolomic disruptions in chronic kidney disease reveals how systemic and localized factors converge to drive CKD progression. These interrelationships underscore the metallome, metabolome, and microbiome’s central role in the disease’s pathogenesis and highlight opportunities for microbiome-based diagnostics and microbiome-targeted interventions (MBTIs).

The development of CKD is fundamentally linked to dysbiosis through multiple interconnected mechanisms collectively termed the gut-kidney axis. Significant alterations in gut microbiome composition, richness, diversity, and blood and fecal metabolic composition have been consistently documented in patients with CKD and kidney failure, strongly supporting a crucial role of gut dysbiosis in the pathogenesis of CKD.[45] Studies have demonstrated that gut bacterial dysbiosis contributes to CKD via several critical mechanisms, including accumulation of uremic toxins, decreased production of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), disturbed enteroendocrine signaling, and development of a leaky gut barrier.[46]

The metabolomic signature of chronic kidney disease represents a complex constellation of altered metabolites reflecting impaired kidney clearance, intestinal dysbiosis, and systemic metabolic derangement. This signature includes elevated protein-derived uremic toxins (PCS, IS, PS, TMAO), small molecular weight retention solutes (urea, creatinine), accumulation of heavy metals, amino acid imbalances, bile acid alterations, and deficiency in beneficial short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). The interplay between these metabolomic changes drives disease progression through multiple pathways involving inflammation, oxidative stress, fibrosis, and vascular dysfunction.[47] Understanding and modulating this metabolomic signature represents a promising therapeutic frontier for slowing CKD progression and improving patient outcomes.

Mismetallation represents a central yet underrecognized mechanism accelerating the progression of chronic kidney disease by allowing toxic heavy metals to displace essential metal cofactors within metalloproteins, metalloenzymes, and mitochondrial complexes. In CKD, impaired renal clearance amplifies the accumulation and bioactivity of cadmium, lead, mercury, arsenic, and chromium, all of which use ionic mimicry to substitute for physiologic metals such as zinc, iron, copper, manganese, and calcium. This displacement collapses antioxidant enzyme systems, impairs mitochondrial ATP generation, and initiates cell death pathways including apoptosis and ferroptosis. The renal proximal tubule, with its high metabolic demand and reliance on metal-dependent enzymatic and mitochondrial functions, is uniquely vulnerable. Mismetallation therefore acts as a unifying pathological process linking heavy metal exposure to oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, vascular injury, hypoxia–signaling dysregulation, and progressive nephron loss in CKD.

Mismetallation occurs through ionic mimicry, whereby toxic heavy metals such as cadmium and lead substitutionally displace essential metal cofactors (calcium, zinc, copper, iron, manganese) from their native metal-binding sites in metalloproteins and metalloenzymes. As a result of this displacement, enzymatic function collapses catastrophically: the displaced redox-active metals become pathologically reactive, generating reactive oxygen species through Fenton-type reactions that damage cellular lipids, proteins, and DNA. This mechanism fundamentally disrupts cellular redox homeostasis, impairing antioxidant enzyme systems that rely on zinc, copper, and iron cofactors such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase.[48]

In the renal proximal tubule, cadmium specifically enters through divalent metal transporter 1 (DMT1) and the calcium/iron uniporter, where it mimics physiological divalent cations by displacing calcium, zinc, and iron from critical intracellular compartments including mitochondria.[49]

This disruption of mitochondrial metal homeostasis directly impairs oxidative phosphorylation capacity, reducing ATP production and compromising the energy-dependent processes essential to renal tubular reabsorption and fluid-electrolyte regulation. The displaced iron and copper subsequently catalyze free radical production via Fenton chemistry, perpetuating oxidative injury within these already-stressed mitochondria. This cadmium-induced mitochondrial dysfunction is particularly consequential in the proximal tubule, where metabolically demanding processes like active transport of ions and organic solutes depend on abundant ATP supply. The accumulation of cadmium in renal tissue reflects the kidney’s critical role in maintaining divalent ion homeostasis, making this organ exceptionally vulnerable to mismetallation-induced injury.[50]

Lead-induced mismetallation occurs through substitution at the metal-binding sites of multiple regulatory proteins, particularly those containing zinc fingers or other metalloproteins critical to transcriptional regulation, DNA repair, and antioxidant enzyme synthesis.[51]

Lead displaces essential trace elements from proteins, including calcium/magnesium-dependent ATPases and zinc-dependent metalloenzymes, disrupting fundamental cellular homeostatic mechanisms. The consequence is heightened oxidative stress through impaired antioxidant enzyme activity and dysregulation of cellular signaling cascades that normally coordinate adaptive responses to environmental challenges. Unlike cadmium, lead’s nephrotoxic effects are amplified through its capacity to generate peroxynitrite (a potent oxidant formed from the interaction of lead-induced superoxide with nitric oxide), further impairing vascular function and renal hemodynamics.

Mitochondria harbor 20–80% of cellular iron, copper, and manganese, which are essential cofactors for electron transport chain (ETC) activity and oxidative phosphorylation.[52]

In CKD, toxic metals such as cadmium enter cells via DMT1 and calcium/iron uniporters, displacing these cofactors from ETC complexes, impairing ATP synthesis, and triggering mitochondrial permeability transition (MPTP), cytochrome c release, and apoptosis—especially in energy-dependent renal proximal tubule cells.[53]

Lead and mercury further disrupt mitochondrial function by displacing zinc and iron from ETC complexes I, III, and IV, inducing excess mitochondrial ROS and ferroptosis—a distinct iron-dependent cell death marked by lipid peroxidation and glutathione peroxidase 4 (GPX4) inactivation.[54][55]

In CKD, impaired clearance of heavy metals exacerbates iron overload, upregulating iron import (e.g., transferrin receptor, DMT1) and downregulating export, creating a pro-ferroptotic intracellular environment.[56]

Metal-induced mitochondrial stress disrupts mitophagy and heightens susceptibility to apoptosis and ferroptosis, synergizing with other CKD stressors—such as proteinuria, hypertension, and systemic inflammation—to accelerate nephron loss and progression to end-stage renal disease.[57].

Nutritional immunity represents a critical arm of host defense in CKD, wherein essential transition metals, including iron, zinc, and manganese, are actively sequestered to prevent microbial proliferation. This metal-withholding strategy is mediated through a range of high-affinity host proteins, including calprotectin, transferrin, lipocalin-2, and hepcidin, which tightly regulate metal availability in both extracellular and intracellular compartments. However, in chronic kidney disease (CKD), over time, this finely tuned network results in a pathological state characterized by functional iron deficiency, zinc and manganese depletion, which collectively exacerbate anemia, promote tissue damage, and increase susceptibility to infection. Understanding how CKD results in these elevated nutritional immunity factors offers key insights into the disease’s complex interplay between immune dysfunction, mineral metabolism, host-pathogen interactions, and potential interventions.

Calprotectin, a heterodimer of S100A8 and S100A9 subunits, serves as a primary innate immune protein markedly elevated in CKD patients due to persistent inflammation and systemic immune activation. [58]

This acute-phase protein contributes to nutritional immunity by sequestering multiple nutrient metals including manganese, zinc, and iron through its hexahistidine (His6) binding sites, though its chronic elevation in CKD may paradoxically impair immunity by simultaneously promoting tissue iron accumulation and exacerbating anemia of chronic disease. [59]

Importantly, elevated calprotectin in CKD associates with both heightened cardiovascular pathology and worsening renal outcomes, as calprotectin levels strongly correlate with cardiovascular events and represent independent predictors of mortality in CKD populations. [60]

The persistent elevation reflects ongoing dysregulation characteristic of uremic states, contributing fundamentally to the pathophysiology of anemia of chronic disease through its iron-sequestering functions.

Lipocalin-2, substantially elevated in CKD patients, plays a complex dual role as both an iron-sequestering host defense protein and a contributor to kidney and cardiovascular injury. [61]

Elevated lipocalin-2 levels in CKD bind bacterial siderophores and prevent bacterial iron acquisition, yet these same proteins have pleiotropic effects including roles in inflammation, metabolic dysfunction, and worsening renal outcomes. [62]

Beyond its bacteriostatic function, LCN2 elevation in CKD stimulates bone-derived fibroblast growth factor 23 (FGF23) production through STAT3/cAMP-mediated signaling, a finding with critical implications for mineral metabolism dysregulation and cardiovascular disease progression. [63]

The relationship between lipocalin-2 elevation and CKD progression remains complex, with evidence suggesting both protective and detrimental effects, depending on the underlying kidney pathology, severity of systemic inflammation, and chronicity.[64][x]

Hepcidin, the master regulator of systemic iron homeostasis, becomes persistently elevated in CKD and represents a key factor in the development of functional anemia.[65]

This hepatic hormone contributes to nutritional immunity by inducing ferroportin degradation in enterocytes and macrophages, thereby sequestering iron in intracellular compartments and restricting pathogen access to this essential nutrient. [66]

However, the hepcidin-ferroportin axis in CKD creates a state of functional iron deficiency despite normal or elevated total body iron stores, where chronic hepcidin elevation ultimately exacerbates both immune dysfunction and tissue iron accumulation in certain compartments. [67]

Chronically elevated hepcidin also results in sustained hypoferremia that impairs erythropoiesis while simultaneously promoting macrophage iron accumulation and pro-inflammatory polarization. [68]

Transferrin, while not an acute-phase protein in the classic sense, undergoes critical dysregulation in CKD as part of the broader iron metabolism disturbance. Normally transferrin saturates to only 30-40% in health, binding iron with extraordinary affinity and preventing free iron from reaching pathogens. [69]

In CKD, transferrin saturation becomes elevated due to dysregulated hepcidin signaling and altered iron absorption kinetics, yet simultaneously transferrin levels may decrease due to protein malnutrition and uremia-induced protein catabolism. [70]

A growing portfolio of mechanistically diverse interventions now targets the dysbiosis–uremic toxin–metallomic triad that characterizes CKD progression. The following section surveys key candidates that act along the gut–kidney axis and at the level of renal cellular biology, including carbon-based adsorbents that sequester uremic solutes in the intestinal lumen, mitochondrial protective agents that constrain oxidative injury, and prebiotic fibers that redirect nitrogen disposal toward the fecal compartment. Additional strategies encompass immunomodulatory and toxin-lowering proteins, biotherapeutic yeasts, and live bacterial therapeutics that restore barrier integrity, suppress pathobionts, and reduce production and systemic absorption of indoxyl sulfate, p-cresyl sulfate, and related metabolites. Finally, metallomic interventions such as dimethylglyoxime (DMG) nickel chelation directly address heavy metal–driven dysbiosis and enzymatic virulence. Together, these approaches exemplify how targeting microbial metabolism, uremic toxin handling, and metal homeostasis may complement or, in selected contexts, delay conventional renal replacement therapies while mitigating systemic complications of CKD.

The most extensively studied category of oral adsorbents represents a foundational approach to reducing uremic toxin accumulation in CKD patients. Activated charcoal functions through adsorption mechanisms, binding uremic toxins within the gastrointestinal tract and preventing their systemic absorption. This approach proves particularly beneficial for CKD patients who cannot efficiently eliminate toxins through impaired renal function.[71]

In a randomized controlled trial, CKD patients receiving 3 g of activated charcoal daily demonstrated marked reductions in serum urea and creatinine over a 12-week period compared to control groups, while patients with ESRD on hemodialysis showed significant reductions in both serum urea and serum phosphorus levels after eight weeks of treatment.[72]

The mechanism involves binding with urea and other urinary toxins, effectively eliminating them via the feces while simultaneously improving dialysis efficiency by removing waste products such as indoxyl sulfate (IS), urea, and other urinary toxins.[73]

Lactulose is a validated microbiome-targeted intervention (MBTI) that operates through a dual mechanism: simultaneously decreasing pathogenic bacterial taxa while increasing short-chain fatty acid (SCFA)-producing bacteria that are characteristically depleted in chronic kidney disease (CKD).[74][75] This targeted approach addresses fundamental dysbiosis mechanisms underlying CKD progression and associated gastrointestinal complications.

Methylene blue represents an emerging neuroprotective and renoprotective agent with demonstrated efficacy in combating cisplatin-induced renal toxicity through multiple mechanisms. Recent studies have shown that methylene blue reduces levels of caspases in tissue, creatinine, and blood urea nitrogen in kidneys, with the protective effect operating through activation of the Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway.[76]

When administered, methylene blue induces mitochondrial hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) production, which activates antioxidant gene expression and upregulates genes involved in the base excision repair (BER) pathway, the main pathway for mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) repair.[77]

The protection of kidney mitochondria from cisplatin-induced damage using methylene blue could significantly expand its therapeutic applications, particularly in scenarios involving drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Beyond its mitochondrial protective effects, methylene blue demonstrates cytoprotective, anti-apoptotic, and antioxidant actions across multiple organ systems.[78]

Gum Arabic (GA) represents a traditional dietary supplement with emerging scientific evidence supporting its efficacy in CKD management. The daily addition of 10-40 g of GA to the diet of patients with ongoing kidney failure substantially decreased C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, which could positively affect patient outcomes and mortality.[79]

Additionally, 90 g of GA per day demonstrated the capacity to decrease hyperglycemia in chronic renal disease patients, addressing one of the major complications associated with CKD progression. Adding GA to drinking water contributes significantly to alleviating kidney problems, independent of its effects on intestinal bacterial ammonia metabolism.[80]

Clinical researchers have hypothesized that GA addition to hemodialysis patients would decrease oxidative stress and reduce the chronic inflammatory activation state associated with hemodialysis procedures. A new regimen combining traditional conservative management of CRF including low protein diet with addition of Acacia gum at 1 g per kg body weight per day has been reported to provide patients with dialysis freedom, representing a potential bridge therapy for patients approaching ESRD who cannot or refuse conventional renal replacement therapy.[81][82]

Lactoferrin, a multifunctional iron-binding glycoprotein found in mammalian breast milk, has demonstrated significant renoprotective and sarcopenia-preventive effects in CKD models. Administration of lactoferrin improved renal function reduction, mitigated renal atrophy and tubulointerstitial damage, and ameliorated skeletal muscle atrophy in CKD mice.[83]

The mechanisms involve attenuation of dysbiosis-induced production of microbiota-derived uremic toxins, thereby reducing indoxyl sulfate accumulation in both blood and muscle tissue, which contributed to decreased renal damage and delayed sarcopenia progression.[84]

Within skeletal muscle specifically, CKD induces aberrant activation of the mTOR1 signaling pathway, impairs autophagy, and disrupts branched-chain amino acid metabolism—abnormalities that were all ameliorated by lactoferrin treatment. The multifaceted mechanisms of lactoferrin suggest it may serve as a comprehensive intervention addressing both renal and systemic complications of advanced CKD.

Saccharomyces boulardii modulates host signaling pathways related to oxidative stress, inflammation, and immunological responses during chronic diseases. In animal models, Saccharomyces boulardii exerts hypoglycemic and antioxidant effects while acting as a renal renin-angiotensin system (RAS) modulator, favoring glomerular morphology and reducing polyuria and albuminuria in diabetic mice.[85]

Saccharomyces boulardii also reduces pathogenic bacteria in feces, confirming its renoprotective effects through multiple mechanisms. Probiotics significantly delay the onset of glucose intolerance, reduce hyperglycemia, dyslipidemia, hepatic steatosis, and oxidative stress, while also slowing the progression of renal dysfunction and reducing inflammatory markers.[86]

The establishment of stable, durable engraftment of transplanted microbiota represents a critical determinant of fecal microbiota transplantation (FMT) efficacy. Nonetheless, FMT represents a promising therapeutic approach for CKD and ESRD by directly addressing the dysbiosis-driven pathophysiology underlying disease progression. The mechanistic rationale is compelling, based on extensive evidence of gut dysbiosis contributions to CKD through RAS activation, inflammation, immune dysregulation, and intestinal barrier dysfunction. Preclinical studies consistently demonstrate that FMT can restore dysbiotic microbiota, suppress inflammation, reduce uremic toxins, and preserve renal function.[87]

Although FMT has not yet been applied to acute kidney injury (AKI), its use in various CKD subtypes—including diabetic nephropathy, IgA nephropathy, membranous nephropathy, and focal segmental glomerulosclerosis—has shown encouraging preclinical and preliminary clinical results.

Psyllium husk represents a naturally occurring, soluble fermentable fiber supplement with emerging evidence supporting its therapeutic potential in chronic kidney disease (CKD) and end-stage renal disease (ESRD). This soluble fiber contains highly branched, gel-forming arabinoxylan compounds that work through the gut-kidney axis to provide multi-faceted renoprotective effects.[88]

The mechanisms through which PSH exerts its beneficial effects are complex and involve modulation of the gut microbiota, restoration of intestinal barrier function, and reduction of systemic inflammation and uremic toxins and enhanced fecal nitrogen excretion.[89][90]

The central mechanism by which psyllium husk benefits CKD patients involves reduction of uremic toxin accumulation through modification of bacterial fermentation pathways and enhanced fecal nitrogen excretion. Small and short-term trials (4-12 weeks duration) of supplemented prebiotics including fiber preparations in people with CKD have reported consistent reduction in uremic toxin levels.[91]

Because uremic toxins are central to the progression of CKD, multiple investigators have hypothesized that fiber supplementation may slow the progression of CKD through reduction of these toxic metabolites. Meta-analyses have consistently demonstrated the uremic toxin-lowering effect of fiber supplementation on multiple critical markers including serum creatinine, p-cresyl sulfate (pCS), and indoxyl sulfate (IS).[92]

Nickel chelation represents a novel approach to managing CKD that specifically targets the metallomic pathology of the disease. The nickel-specific chelator dimethylglyoxime (DMG) offers a mechanistically distinct intervention by removing a heavy metal that contributes to dysbiosis, virulence, and systemic toxicity. This represents a direct link between metallomic dysfunction and dysbiosis in CKD. The mechanism involves nickel-induced oxidative stress that promotes the growth of pathogenic bacteria while suppressing beneficial commensals. Furthermore, nickel exposure correlates with elevated serum uric acid levels, creating a secondary pathway for kidney disease progression.[93]

The therapeutic application of DMG involves oral delivery of non-toxic levels of the chelator. In experimental models, DMG inhibits the activity of nickel-containing enzymes—urease, glyoxylase, and hydrogenase—which are critical for the survival and virulence of multi-drug resistant enteric pathogens.[94]

CKD patients often show an expansion of Proteobacteria (including Escherichia coli, Salmonella, etc.) and other pathobionts, alongside a loss of beneficial anaerobes. This shift is associated with impaired gut barrier function and increased permeability, allowing bacteria and endotoxins like lipopolysaccharides (LPS) to translocate into circulation. The dysbiotic flora generates excessive uremic toxins (notably indoxyl sulfate and p-cresyl sulfate) from dietary protein, which accumulate due to reduced renal clearance and contribute to oxidative stress, inflammation, and fibrosis in CKD.

Given these gut-kidney axis perturbations and dysbiosis, interventions like Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) are explored as EcN favorably modulate the CKD gut through four key actions: (1) competitive advantage over pathogenic microbes, (2) modulation of the microbiota toward eubiosis, (3) anti-inflammatory and barrier-protective effects, and (4) reduction of uremic toxin production and absorption.

Preclinical studies provide proof-of-concept that EcN and similar probiotics can benefit the CKD gut-kidney axis. In rodent models of CKD, probiotic interventions have led to lowered uremic toxin levels, improved gut barrier integrity, and preservation of renal function.[95] While many studies use multi-strain formulations, the specific contributions of EcN’s capabilities (pathogen suppression, SCFA promotion, etc.) are clearly documented in related models of gut inflammation.[96]

Vitamin D3 supplementation significantly reduces both hepcidin and ferritin levels in CKD children, with hepcidin levels dropping by 42.94 ng/mL versus rising by 4.58 ng/mL in placebo groups. This effect occurs through vitamin D’s suppression of IL-6-mediated hepcidin induction and restoration of normal iron metabolism and regulation.[97]

The anti-C5 monoclonal antibody eculizumab has made it possible to reverse even advanced atypical hemolytic-uremic syndrome (aHUS) kidney failure. In clinical studies, the majority of aHUS patients on dialysis who received eculizumab were able to discontinue dialysis as their kidneys healed. In one series, 4 of 5 dialysis-dependent patients recovered kidney function with continued eculizumab therapy.

Eculizumab halts the complement attack on the renal microvasculature, allowing endothelial cells to recover and nephrons to resume filtering – often to a remarkable degree if therapy is started promptly.[98][99]

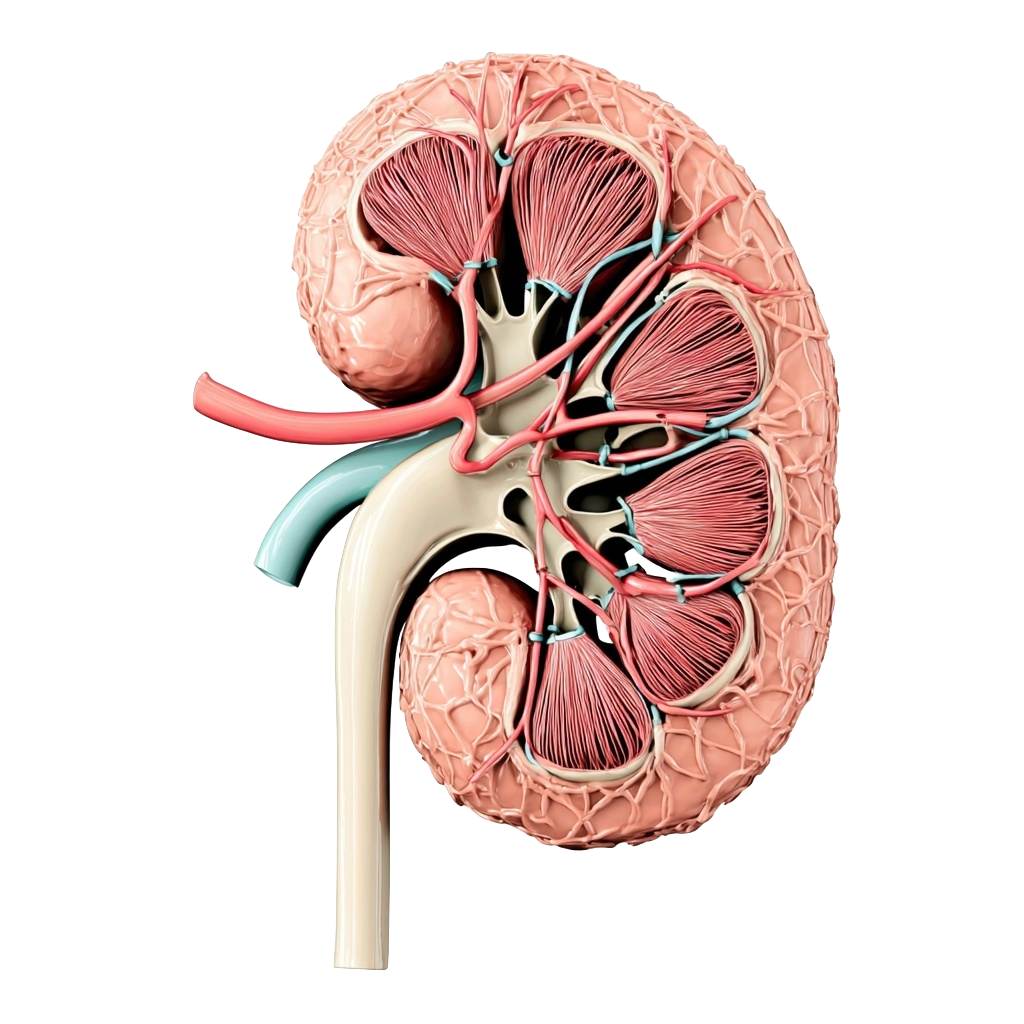

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a progressive condition characterized by a gradual decline in kidney function, often remaining asymptomatic in its early stages but potentially leading to kidney failure.[100] Globally, CKD affects over 10% of the population, representing a significant public health challenge.[101] The condition is formally defined by the presence of irreversible structural or functional damage to the kidneys.[102]

The disease is recognized as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality worldwide, contributing to millions of disability-adjusted life years and deaths annually.[103] Beyond kidney dysfunction itself, patients with CKD experience altered mineral metabolism, anemia, metabolic acidosis, and significantly increased cardiovascular events that worsen their overall health outcomes and quality of life.

At the cellular and tissue level, key pathological features of CKD include nephron loss, inflammation, activation of myofibroblasts, and the deposition of extracellular matrix.[104] These pathological changes drive the progressive scarring and fibrosis of kidney tissue, ultimately leading to irreversible kidney damage. As CKD progresses, the kidneys’ ability to effectively eliminate metabolic wastes and environmental toxicants—such as heavy metals including arsenic, cadmium, lead, and mercury—becomes severely compromised.[105]

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Did you know?

Short-chain fatty acids produced by gut microbes supply up to seventy percent of the energy used by colonocytes, making them fundamental regulators of intestinal barrier integrity and inflammation.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

Gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is strongly linked to cardiovascular disease, potentially influencing atherosclerosis more than cholesterol, making the gut microbiome a key therapeutic target.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Microbes are microscopic organisms living in and on the human body, shaping health through digestion, vitamin production, and immune protection. When microbial balance is disrupted, disease can occur. This guide explains the key types of microorganisms—bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and archaea—along with major examples of pathogenic and beneficial species.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

Gut microbiota-derived metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) is strongly linked to cardiovascular disease, potentially influencing atherosclerosis more than cholesterol, making the gut microbiome a key therapeutic target.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

Did you know?

The bidirectional relationship between diabetes and CKD creates a vicious cycle in which each condition perpetuates the other. Diabetic patients who develop CKD show accelerated progression of kidney disease and markedly increased cardiovascular event rates compared to nondiabetic CKD populations.

Did you know?

Short-chain fatty acids produced by gut microbes supply up to seventy percent of the energy used by colonocytes, making them fundamental regulators of intestinal barrier integrity and inflammation.

Alias iure reprehenderit aut accusantium. Molestiae dolore suscipit. Necessitatibus eum quaerat. Repudiandae suscipit quo necessitatibus. Voluptatibus ullam nulla temporibus nobis. Atque eaque sed totam est assumenda. Porro modi soluta consequuntur veritatis excepturi minus delectus reprehenderit est. Eveniet labore ut quas minima aliquid quibusdam. Vitae possimus fuga praesentium eveniet debitis exercitationem deleniti.

2025-11-25 19:11:11

Chronic Kidney Disease (CKD) majorpublished

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Anemia is a reduction in red blood cells or hemoglobin, often influenced by the gut microbiome's impact on nutrient absorption.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Anemia is a reduction in red blood cells or hemoglobin, often influenced by the gut microbiome's impact on nutrient absorption.

Transition metals like iron, zinc, copper, and manganese are crucial for the enzymatic machinery of organisms, but their imbalance can foster pathogenic environments within the gastrointestinal tract.

TMAO is a metabolite formed when gut bacteria convert dietary nutrients like choline and L-carnitine into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized in the liver to TMAO. This compound is linked to cardiovascular disease, as it promotes atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and inflammation, highlighting the crucial role of gut microbiota in influencing heart health.

Transition metals like iron, zinc, copper, and manganese are crucial for the enzymatic machinery of organisms, but their imbalance can foster pathogenic environments within the gastrointestinal tract.

Microbiome Targeted Interventions (MBTIs) are cutting-edge treatments that utilize information from Microbiome Signatures to modulate the microbiome, revolutionizing medicine with unparalleled precision and impact.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

TMAO is a metabolite formed when gut bacteria convert dietary nutrients like choline and L-carnitine into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized in the liver to TMAO. This compound is linked to cardiovascular disease, as it promotes atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and inflammation, highlighting the crucial role of gut microbiota in influencing heart health.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Nutritional immunity restricts metal access to pathogens, leveraging sequestration, transport, and toxicity to control infections and immunity.

Nutritional immunity restricts metal access to pathogens, leveraging sequestration, transport, and toxicity to control infections and immunity.

Dimethylglyoxime represents a novel therapeutic paradigm that exploits a fundamental metabolic difference between pathogenic bacteria and their mammalian hosts. By selectively depleting bacterial access to nickel, a cofactor essential for multiple pathogenic enzymes but unnecessary for human physiology, DMG offers a theoretically host-sparing antimicrobial approach.

Lactulose functions as a validated microbiome-targeted intervention for CKD by suppressing dominant pathogenic taxa such as Escherichia-Shigella while enriching depleted SCFA-producing bacteria like Bifidobacterium. This dual modulation reduces uremic toxin generation, restores intestinal function, and mechanistically slows CKD progression through targeted correction of dysbiosis.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Lactoferrin (LF) is a naturally occurring iron-binding glycoprotein classified as a postbiotic with immunomodulatory, antimicrobial, and prebiotic-like properties.

Fecal Microbiota Transplantation (FMT) involves transferring fecal bacteria from a healthy donor to a patient to restore microbiome balance.

Dimethylglyoxime represents a novel therapeutic paradigm that exploits a fundamental metabolic difference between pathogenic bacteria and their mammalian hosts. By selectively depleting bacterial access to nickel, a cofactor essential for multiple pathogenic enzymes but unnecessary for human physiology, DMG offers a theoretically host-sparing antimicrobial approach.

Escherichia coli (E. coli) is a versatile bacterium, from gut commensal to pathogen, linked to chronic conditions like endometriosis.

Lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a potent endotoxin present in the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria that causes chronic immune responses associated with inflammation.

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) is a rare, non-pathogenic strain of E. coli discovered during World War I from a soldier who did not get dysentery while others did. Unlike harmful E. coli, EcN acts as a probiotic: it settles in the gut, competes with bad bacteria for food and space, produces natural antimicrobials, and even helps strengthen the gut barrier.

Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 (EcN) is a highly regarded probiotic strain with significant clinical value due to its ability to outcompete a wide range of pathogenic microorganisms in the gastrointestinal tract. Through the formation of robust biofilms on intestinal epithelial surfaces, EcN effectively blocks the adhesion and colonization of pathogens such as Salmonella, Shigella, and Klebsiella pneumoniae.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Recent research has revealed that specific gut microbiota-derived metabolites are strongly linked to cardiovascular disease risk—potentially influencing atherosclerosis development more than traditional risk factors like cholesterol levels. This highlights the gut microbiome as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular interventions.

TMAO is a metabolite formed when gut bacteria convert dietary nutrients like choline and L-carnitine into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized in the liver to TMAO. This compound is linked to cardiovascular disease, as it promotes atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and inflammation, highlighting the crucial role of gut microbiota in influencing heart health.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Microbes are microscopic organisms living in and on the human body, shaping health through digestion, vitamin production, and immune protection. When microbial balance is disrupted, disease can occur. This guide explains key microbe types—bacteria, viruses, fungi, protozoa, and archaea—plus major pathogenic and beneficial examples.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Recent research has revealed that specific gut microbiota-derived metabolites are strongly linked to cardiovascular disease risk—potentially influencing atherosclerosis development more than traditional risk factors like cholesterol levels. This highlights the gut microbiome as a novel therapeutic target for cardiovascular interventions.

TMAO is a metabolite formed when gut bacteria convert dietary nutrients like choline and L-carnitine into trimethylamine (TMA), which is then oxidized in the liver to TMAO. This compound is linked to cardiovascular disease, as it promotes atherosclerosis, thrombosis, and inflammation, highlighting the crucial role of gut microbiota in influencing heart health.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Heavy metals influence microbial pathogenicity in two ways: they can be toxic to microbes by disrupting cellular functions and inducing oxidative stress, and they can be exploited by pathogens to enhance survival, resist treatment, and evade immunity. Understanding metal–microbe interactions supports better antimicrobial and public health strategies.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Dysbiosis in chronic kidney disease (CKD) reflects a shift toward reduced beneficial taxa and increased pathogenic, uremic toxin-producing species, driven by a bidirectional interaction in which the uremic environment disrupts microbial composition and dysbiotic metabolites accelerate renal deterioration.

Short-chain fatty acids are microbially derived metabolites that regulate epithelial integrity, immune signaling, and microbial ecology. Their production patterns and mechanistic roles provide essential functional markers within microbiome signatures and support the interpretation of MBTIs, MMAs, and systems-level microbial shifts across clinical conditions.

Z. Ea, A. Sm, A. Nm, and K. Mo

Assembled human microbiome and metabolome in chronic kidney disease: Dysbiosis a double-edged sword interlinking Circ-YAP1, Circ-APOE & Circ-SLC8A1Toxicol Rep. 2025 May 29;14:102058.

J. Kemp, M. Ribeiro, N. Borges, L. Cardozo, D. Fouque, and D. Mafra,

Dietary Intake and Gut Microbiome in Chronic Kidney Disease.American Society of Nephrology. Clinical Journal, Mar. 2025

I. L. Suliman et al.

Gut Microbiome in Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease Stages 4 and 5: A Systematic Literature ReviewInternational Journal of Molecular Sciences, Nov. 2025

M. Laiola et al.

Toxic microbiome and progression of chronic kidney disease: insights from a longitudinal CKD-Microbiome StudyGut, Jun. 2025

W. h. W. Tang, T. Kitai, and S. L. Hazen.

Gut Microbiota in Cardiovascular Health and DiseaseLippincott Williams & Wilkins, Mar. 2017.

Marx-Schütt K, Cherney DZI, Jankowski J, Matsushita K, Nardone M, Marx N.

Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease.Eur Heart J. 2025 Jun 16;46(23):2148-2160.

Noels H, van der Vorst EPC, Rubin S, Emmett A, Marx N, Tomaszewski M, Jankowski J.

Renal-Cardiac Crosstalk in the Pathogenesis and Progression of Heart Failure.Circ Res. 2025 May 23;136(11):1306-1334.

Ali WB, Tariq T, Raashid Sidhu A, Anan S, Jannat S, Tayyab M, Ahmad M, Mushtaq U.

Silent Myocardial Ischemia in CKD Stage 3-5: Prevalence and Predictors.Cureus. 2025 Sep 11;17(9):e92107.

Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, Lian F.

The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease.Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 28;14:1149239.

Portincasa, P., Bonfrate, L., Vacca, M., De Angelis, M., Farella, I., Lanza, E., Khalil, M., Wang, D. Q.-H., Sperandio, M., & Di Ciaula, A.

Gut Microbiota and Short Chain Fatty Acids: Implications in Glucose Homeostasis.International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 23(3), 1105. (2022)

Zhao X, An X, Yang C, Sun W, Ji H, Lian F.

The crucial role and mechanism of insulin resistance in metabolic disease.Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023 Mar 28;14:1149239.

Chao CT, Hou YC, Liao MT, Tsai KW, Hung KC, Shih LJ, Lu KC.

Adynamic bone disorder in chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis and narrative review of potential biomarkers as diagnosis and therapeutic targets.Ren Fail. 2025 Dec;47(1):2530162.

Mihai S, Codrici E, Popescu ID, Enciu AM, Albulescu L, Necula LG, Mambet C, Anton G, Tanase C.

Inflammation-Related Mechanisms in Chronic Kidney Disease Prediction, Progression, and Outcome.J Immunol Res. 2018 Sep 6;2018:2180373.

Chao CT, Hou YC, Liao MT, Tsai KW, Hung KC, Shih LJ, Lu KC.

Adynamic bone disorder in chronic kidney disease: meta-analysis and narrative review of potential biomarkers as diagnosis and therapeutic targets.Ren Fail. 2025 Dec;47(1):2530162.

Liu W, Gu W, Chen J, Wang R, Shen Y, Lu Z, Zhang L.

Global, regional and national epidemiology of anemia attributable to chronic kidney disease, 1990-2021.Clin Kidney J. 2025 May 19;18(5):sfaf138.

Fu LZ, Chen HF, Shen YH, Zhang XL, Tang F, Hu XX, Liu ZJ, Ouyang WW, Liu XS, Wu YF.

Time-updated patterns of hemoglobin and hematocrit and the risk of CKD progression.Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025 Oct 30;16:1642307.

Fu LZ, Chen HF, Shen YH, Zhang XL, Tang F, Hu XX, Liu ZJ, Ouyang WW, Liu XS, Wu YF.

Time-updated patterns of hemoglobin and hematocrit and the risk of CKD progression.Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2025 Oct 30;16:1642307.

Prapaiwong P, Ruksakulpiwat S, Jariyasakulwong P, Kasetkala P, Puwarawuttipanit W, Pongsuwun K.

Determinants of Anemia Among Patients with Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review of Empirical Evidence.J Multidiscip Healthc. 2025 Jun 28;18:3765-3780.

Pei X, Bakerally NB, Wang Z, Bo Y, Ma Y, Yong Z, Zhu S, Gao F, Bei Z, Zhao W.

Kidney function and cognitive impairment: a systematic review and meta-analysis.Ren Fail. 2025 Dec;47(1):2463565.

Pei X, Bakerally NB, Wang Z, Bo Y, Ma Y, Yong Z, Zhu S, Gao F, Bei Z, Zhao W.